A Lifetime Of Motherless Mother’s Days

Three sisters remember their mother and the day that changed their lives forever

It’s May. The sun bathes the Toombs County landscape in a perfect, shimmering light. The trees have leafed out. The flowers dance along dirt roads releasing their sweet fragrance into the air and adding their vibrant colors to the countryside. For those of us who love nature and the great outdoors, May is the most sacred of months.

“I love to spend time out in my yard,” says Joy Weaver, a self-described outdoor person. “I just love flowers and gardening.”

But instead of welcoming and celebrating May with the other gardeners of the world, Joy is anxious and finds herself holding her breath. This uneasy emotional response stems from the second Sunday of the month — Mother’s Day, the day the world slows down to honor mothers, motherhood, maternal bonds and the positive influence mothers have on the world. But for Joy Weaver — and for other children and adults whose mothers have died — Mother’s Day is a painful reminder of great loss.

Her mother, Linda Sue Jernigan, was taken from the world on March 3, 1979 when Joy was just 10 years old.

“Her boyfriend killed her,” she says. “My mother was in a [verbally and physically] abusive relationship with a man, and the relationship ended on the day he shot continued from page

her in the head. It was a long time ago, but it still hurts. It has never stopped hurting, and it never will. My sisters and I had to grow up without our mama.”

Folks like Joy seem to hold it together most of the year, but the lead up to Mother’s Day can be agonizing. The endless advertisements. The commercials showcasing happy families showering “mom” with gifts. The special church services. The Mother’s Day brunches. The greeting cards. The office chit-chat about get-togethers. The syrupy sweet social media posts. The happiness and laughter.

The Mother’s Day hoopla leaves Joy and her two sisters feeling cheated, as they relive the trauma of their mother’s death, the funeral, the trial, and the second trial, over and over again — an infinite loop of sadness and pain. And they realize that a lifetime has passed without the thousands of memories most families make and share.

Joy marks the day with a visit to Pinecrest Cemetery.

“I always take flowers to her grave on Mother’s Day, and I’ve already bought them [for this year],” says Joy. “I wonder what she would look like today, and I wonder what she and I would talk about if she was here.”

“I have to stay off of Facebook during that time,” says Marla Jernigan, Joy’s youngest sister who was seven at the time of her mother’s death. “It’s just too much for me. I wish I could call her. I wish I could have known her. I wish my son could have known her. I isolate myself.”

The sisters, including their middle sister, Jeannie Morris, have dealt with the trauma of losing their mother to gun violence for 44 years, and though time is certainly an important factor in the healing process, time, on its own, is not a universal healer, and Mother’s Day never gets easier.

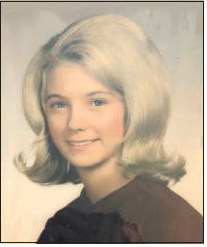

“Time does not heal,” Marla adds. “It helps, but it doesn’t heal. It never leaves my mind. I guess the older I get, the angrier I get.” Blonde and Beautiful

Linda Sue Jernigan was born on February 28, 1951, to Bennie and Cleta Jernigan of Toombs County. Her siblings were Ouida, Ann, Mary Nell, Bennie Ray, Benjamin, and Lisa Jernigan.

“Mama was born in Vidalia,” Joy notes. “I think there was a hospital somewhere in downtown back then, and I remember someone pointing to a building one time and saying that my mama was born there.” Joy and her sisters were so young when their mother died that they only have limited memories and a few tokens from her 28-year life. They rely on a handful of photographs of their mother to help them remember.

One faded color picture shows a very young, very blonde, Linda with her dog, Lady. Another patched together with tape, showcases Linda as a sunkissed horseback rider with striped capris. Two black and white photos taken in a field somewhere feature Linda — maybe eight or nine years old — alongside more horses. It’s easy to see that Linda Jernigan loved the company of animals.

“I remember that she really liked dogs,” Joy says. “We always had a dog. One day she came home with a German Shepherd puppy. We named him, Sherman, and he went everywhere with us. I remember him following us through the woods. I remember Mama driving the truck and all of us looking at him riding in the back of the truck as we rode down the road.”

As the oldest, Joy is blessed with more memories than her two younger sisters. She says that when she tries, she can pull up the happy times in her mind.

“Mama was always smiling and always laughing,” she recalls. “She was positive and upbeat and had a playful nature about her.”

“She told us ghost stories,” middle sister, Jeannie Morris, adds. “She would drape a sheet over her head and talk into a box fan so that her voice was weird and spooky, and we loved it when she did that. And she’d run and jump and slap the pull chain on light bulbs on the ceiling with her hand.”

Another photo spotlights Jernigan’s million dollar grin and her striking eyes — like two large sapphires reflecting a deep, blue sea.

“She had beautiful teeth,” says Jeannie. “Mama would drive her car around, and I’d stand in the front seat beside her. I thought I was something. That’s another thing I remember.”

Linda Jernigan became a young, single mom at just 17. To make ends meet, she moved in with her grandmother, Mary Jernigan, in the Center community. In her twenties, Linda went to work at Pinegrove Apparel, and her daughters aren’t sure, but they think their mother operated a sewing machine. The sisters are certain of one thing: Money was tight.

“One time, she had some extra money, and we went to Piggly Wiggly to get groceries,” Joy says. “She told us that each of us could buy two little things, and that was a real treat for us. We bought a Sarah Lee pound cake and some ice cream that day, and we went outside and had a picnic together.”

Joy speaks of the moment as if it happened yesterday.

“Sometimes she took us to the store in Center and bought us Vienna sausages in a can and Reese’s Cups,” Marla says. “And I remember taking long walks in the woods with her. We would walk and play underneath the pine trees until just before dark.”

In a years before there was a bathroom in her grandmother’s house, Linda Jernigan heated water on the stovetop in four big pots before pouring the water into a galvanized tub for her daughters to take their baths.

“We drew straws to determine who got to bathe first,” Joy remembers. “None of us wanted to bathe last because the water was dirty and cold by then.”

And Joy recollects her mother picking a splinter out of her finger with a needle, rubbing the splinter in her hair, and saying that by rubbing it in her hair, the wound wouldn’t get sore. She says that her mother’s ritual worked — her finger didn’t hurt afterwards.

“And she let us play in the ditch after it rained and the ditch had filled up with water,” Jeannie adds.

The girls mention that their mother read a lot and always had a book in her hands.

“I love to read, too,” says Joy. “And Mama kept things clean and in order. Her car was immaculate. Looking back, I think my mother had OCD [Obsessive Compulsive Disorder], and a several years ago, I realized I have OCD, too. I guess I inherited that trait from her.”

Linda Jernigan had a nickname for each of her three little girls. She called Joy, “Big Girl,” because she was the oldest daughter. Her nickname for her middle daughter, Jeannie, was “Lovell,” and Marla was known as, “Froggie,” because she liked watching Kermit the Frog on Sesame Street.

“My memories of Mama are more like feelings — like love,” Marla says. “I know she loved us. That’s something I remember about her — the love.”

Few, but powerful, are the precious memories of three motherless women who lost their beloved mother at such a young, fragile age.

“We all feel her presence,” Joy adds. “I think she’s proud of us, and I think she’s smiling down on all of us.”

The Day the World Changed In March 1979, the sisters were young, innocent, little girls who sang songs, danced, played with dolls, attended Lyons Elementary School, and along with their mother, lived with their great-grandmother, Mary Jernigan, in the Center community. Joy was 10, Jeannie was nine, and Marla was seven when their world fell apart.

Lisa Jernigan Foskey lived next door.

“Linda was my sister,” Lisa says. “She was 16 when I was born, so I am close in age to her daughters. [Joy, Jeannie, and Marla] have always been more like my sisters than my nieces.”

Lisa replays the events of the day her sister was shot.

“It was a Saturday, and Joy and I had walked next door,” Lisa remembers. “[As we left the house], we saw Linda sitting in the passenger seat of his car, and he was in the driver’s seat. They were sitting in there arguing. They always argued. There was always chaos. That was nothing new for us to witness.”

From a nearby house, Lisa and Joy heard the loud echo of a gunshot.

“We lived out in the country, and we heard shooting sometimes, so we weren’t instantly alarmed by the sound,” she says.

But in the next minute, they heard Mary Jernigan’s wild, wailing screams. As the little girls ran back toward the house, they saw the car speeding away.

“I remember seeing my mother run into the yard, and I watched my grandmother [Mary Jernigan] tell her something,” Lisa remembers. “And I saw my mother fall to her knees. She just fell out there. And we were young, but we knew something horrible had just happened.”

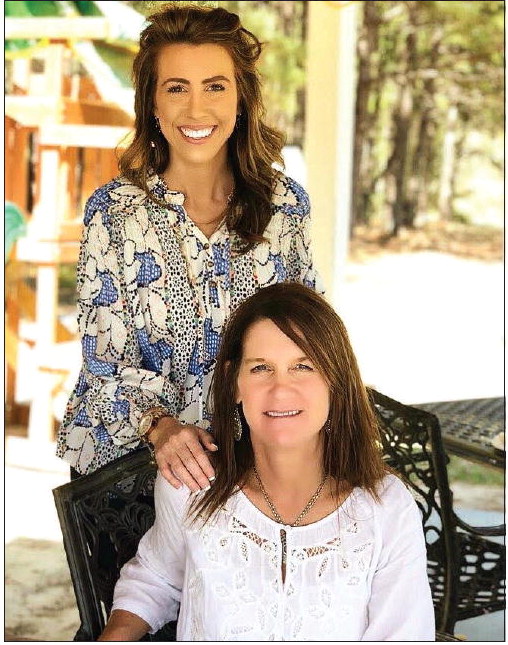

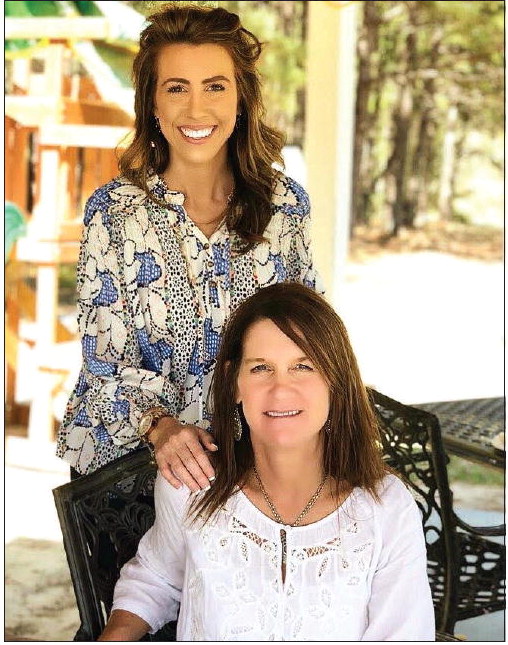

Linda Jernigan’s three daughters and her granddaughters. From left to right: Lindsay Tillman, Marla Jernigan-Eason, Joy Weaver, Jeannie Morris, Jessie Morris, and Jadyn Morris.

Linda Sue Jernigan